For the past year, my team and I have been working on a personalized user experience in the Taboola feed. We used Multi-Task Learning (MTL) to predict multiple Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) on the same set of input features, and implemented a Deep Learning (DL) model in TensorFlow to do so. Back when we started, MTL seemed way more complicated to us than it does now, so I wanted to share some of the lessons learned.

There are already quite a few posts about implementing MTL in a DL model (1, 2, 3).

In this post I will share some specific points to consider when implementing MTL in a Neural Network (NN). I will also present simple TensorFlow solutions to overcome the discussed issues.

Sharing is caring

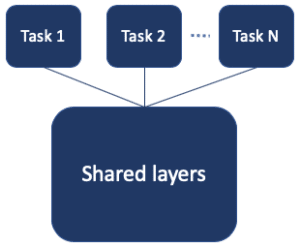

We wanted to start with the basic approach of hard parameter sharing. Hard sharing means we have a shared subnet, followed by task-specific subnets.

An easy way to start playing with such a model in TensorFlow is using Estimators with multiple heads. Since it doesn’t look that different than other NN architectures, you may ask yourself what could go wrong?

Lesson 1 – Combining losses

The first challenge we encountered with our MTL model, was defining a single loss function for multiple tasks. While a single task has a well defined loss function, with multiple tasks come multiple losses.

The first thing we tried was simply to sum the different losses. Soon enough we could see that while one task converges to good results, the others look pretty bad. When taking a closer look, we could easily see why. The losses’ scales were so different, that one task dominated the overall loss, while the rest of the tasks didn’t have a chance to affect the learning process of the shared layers.

A quick fix was replacing the sum of losses with a weighted sum, that brought all losses to approximately the same scale. However, this solution involves another hyperparameter that might need to be tuned every once in a while.

Luckily, we found a great paper proposing to use uncertainty to weigh losses in MTL. The way it is done, is by learning another noise parameter that is integrated in the loss function for each task. This allows having multiple tasks, possibly regression and classification, and bringing all losses to the same scale. Now we could go back to simply summing our losses.

Not only did we get better results than with a weighted sum, we could forget about the additional weights hyperparameters. Here is a Keras implementation provided by the authors of the paper.

Lesson 2 – Tuning learning rates

It’s a common convention that learning rate is one of the most important hyperparameters for tuning neural networks. So we tried tuning, and found a learning rate that looked really good for task A, and another one that was really good for task B. Choosing the higher rate caused dying Relu’s on one of the tasks, while using the lower one brought a slow convergence on the other task. Then what could we do? We could tune a separate learning rate for each of the “heads” (task-specific subnets), and another rate for the shared subnet.

Though it may sound complicated, it’s actually pretty simple. Usually when training a NN in TensorFlow you use something like:

optimizer = tf.train.AdamOptimizer(learning_rate).minimize(loss)

AdamOptimizer defines how gradients should be applied, and minimize computes and applies them. We can replace minimize with our own implementation that would use the appropriate learning rate for each variable in our computational graph when applying the gradients:

all_variables = shared_vars + a_vars + b_vars all_gradients = tf.gradients(loss, all_variables) shared_subnet_gradients = all_gradients[:len(shared_vars)] a_gradients = all_gradients[len(shared_vars):len(shared_vars + a_vars)] b_gradients = all_gradients[len(shared_vars + a_vars):] shared_subnet_optimizer = tf.train.AdamOptimizer(shared_learning_rate) a_optimizer = tf.train.AdamOptimizer(a_learning_rate) b_optimizer = tf.train.AdamOptimizer(b_learning_rate) train_shared_op = shared_subnet_optimizer.apply_gradients(zip(shared_subnet_gradients, shared_vars)) train_a_op = a_optimizer.apply_gradients(zip(a_gradients, a_vars)) train_b_op = b_optimizer.apply_gradients(zip(b_gradients, b_vars)) train_op = tf.group(train_shared_op, train_a_op, train_b_op)

By the way, this trick can actually also be useful for single-task networks.

Lesson 3 – Using estimates as features

Once we’re past the first phase of creating a NN that predicts multiple tasks, we might want to use our estimate for one task as a feature to another. In the forward-pass that’s really easy. The estimate is a Tensor, so we can wire it just like any other layer’s output. But what happens in backprop?

Say the estimate for task A is passed as a feature to task B. We probably wouldn’t want to propagate the gradients from task B back to task A, as we already have a label for A.

Don’t worry, TensorFlow’s API has tf.stop_gradient just for that reason. When computing the gradients, it lets you pass a list of Tensors you wish to treat as constants, which is exactly what we need.

all_gradients = tf.gradients(loss, all_variables, stop_gradients=stop_tensors)

Again, this is useful in MTL networks, but not only. This technique can be used whenever you want to compute a value with TensorFlow, and need to pretend that the value was a constant. For example, when training Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), you don’t want to backprop through the generation process of the adversarial example.

So, what’s next?

Our models are up and running and Taboola feed is being personalized. However, there is still a lot of room for improvement, and lots of interesting architectures to explore. In our use case, predicting multiple tasks also means we make a decision based on multiple KPIs. That can be a bit more tricky than using a single KPI… but that’s already a whole new topic.

Thanks for reading, I hope you found this post useful!